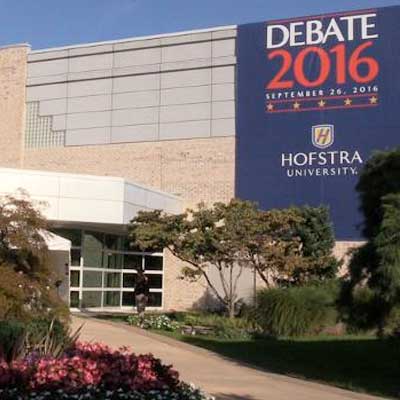

A student conducting research. The friend who convinced you to join a new club or participate in a community service project. The professor who inspired you. They’re all HU World Changers. Being an HU World Changer is about the impact you have on what’s right in front of you – big or small. Tell us how you’re changing the world or tell us about someone who’s changing YOUR world. Share your story on social media using #HUWorldChanger.