The Degree for You

Our Programs

There are a variety of undergraduate and graduate programs at the

School of Education including

teacher education, leadership,

literacy studies, and

special education.

For Students

Resources

Students in the School of Education have access to a wealth of resources, including state-of-the-art facilities like the STEM Studio; support from the Office of Field Placement and the School of Education Dean's Office; valuable internship opportunities; professional workshops; and The Joan and Arnold Saltzman Community Services Center, which provides unique research and training opportunities.

Latest Updates

Serving the Community

Outreach

The School of Education offers

a variety of services for educators

including programs for local students

through the Center for Educational Access & Success, and classroom plans from the Center for STEM Research.

Explore Your

Career Potential

How much can you expect to earn?

How long will it take to find a job?

Theta Beta Chapter

Kappa Delta Pi

Kappa Delta Pi (KDP) is an international honor society in education, founded in 1911, that recognizes and celebrates scholarship and excellence in education, fostering fellowship among those dedicated to teaching and service.

School of Education Office of Professional Development

Buildings and Facilities

Virtual Tour

Can’t make it to campus? Visit our virtual tour and see what makes the School of Education so special.

What's Next

Our Alumni

Meet some of the students now working in education who got their start at Hofstra, and see what the future holds for a student with a degree from the School of Education.

Selected School of Education Experts

Our experts are available to respond to qualified inquiries from journalists, conference organizers, and more. Expert profiles below contain detailed biographical information and media files to help you find the most relevant expert for your needs. Use the search bar to refine your search by name, expertise, or affiliation. On Deadline? If you are a journalist, please inform us of deadline requests and we will respond promptly.

STEPHEN HERNANDEZ

Associate Professor of

Specialized Programs in Education

Stephen Hernandez is a specialist in teacher certification, special education and early childhood special education.

• Collaboration

• Special Education

• Teacher Certification

• Early Childhood Special Education

BIO and CONTACT INFO

ROBERTO JOSEPH

Associate Professor of

Teaching, Learning and Technology

Roberto Joseph is a specialist in

technology in the classroom.

• Educational Technology

• Gaming and App Development

as a K-12 Teaching Tool

• Culture, Learning and Technology

BIO and CONTACT INFO

ALAN J. SINGER

Professor of

Teaching, Learning and Technology

Alan Singer specializes in social studies education and United States history.

• Social Studies Education

• United States History

• History of Slavery

• Teaching race, ethnicity, and class

BIO and CONTACT INFO

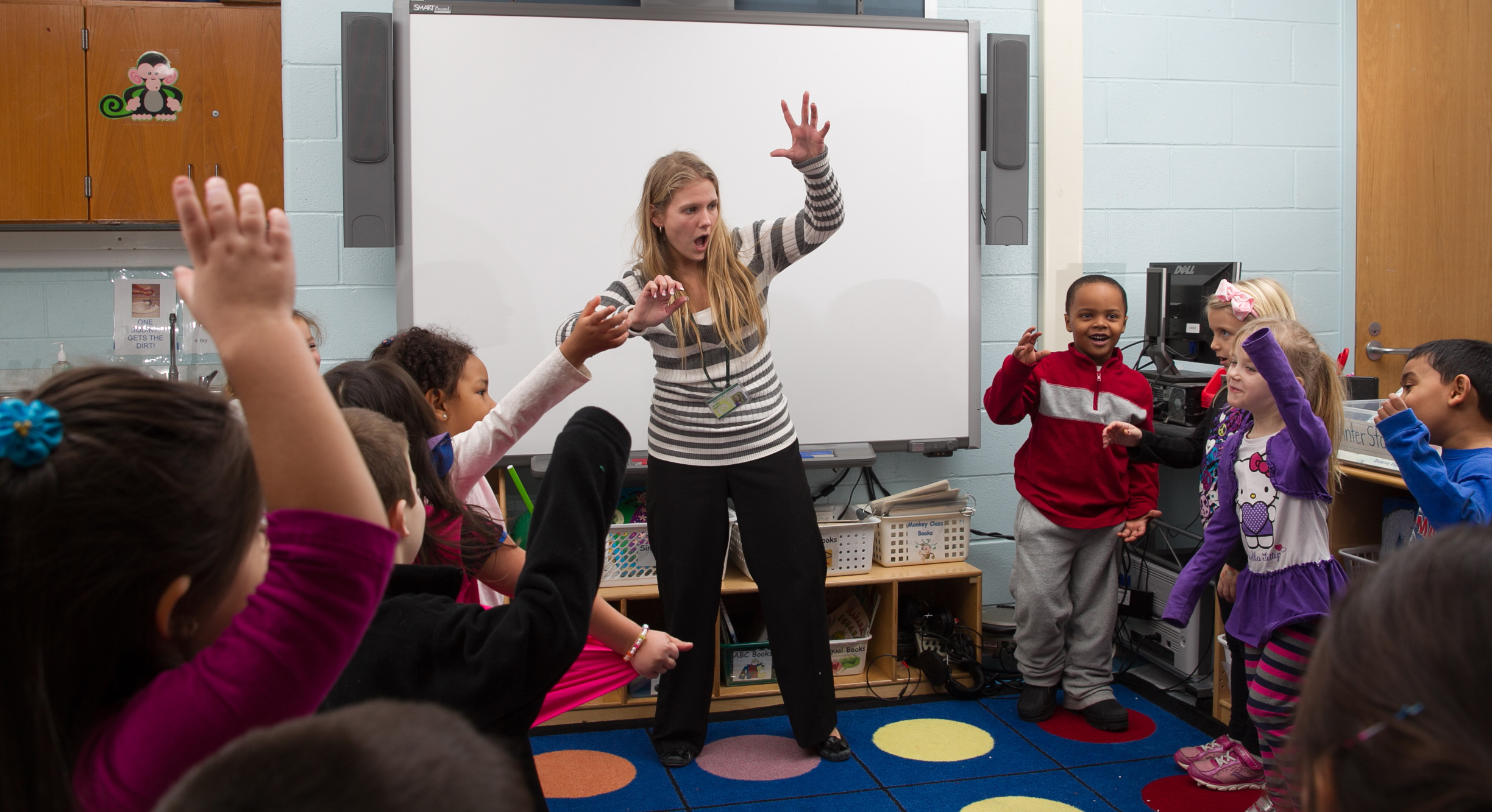

About the School

The faculty of the Hofstra University School of Education are dedicated to the preparation of reflective and knowledgeable professionals who use scholarship to inform their practice. Collectively, we strive toward a more just, open, and democratic society as we collaborate with and learn from children, adolescents, and adults in diverse social and cultural settings.